What are floaters?

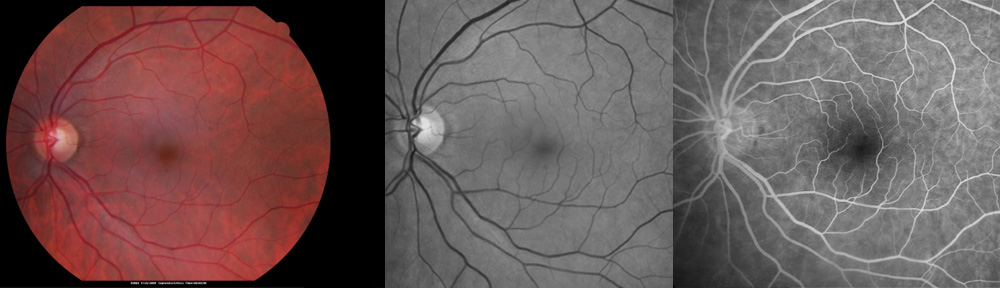

Floaters are small specks, fibers, or bug-shaped objects that may appear to move in front of your eye. At times they may appear like a veil or cloud moving in the vision. Floaters differ from blind spots in the vision in that floaters have some degree of independent movement. Blind spots are missing areas in the vision that move precisely with eye movement. Although floaters do follow the movement of the eye, there is usually some degree of continued movement after the eye stops moving. They are frequently seen when looking at a blank wall or blue sky. Floaters are actually tiny clumps of fiber or cellular debris within the jelly-like fluid (vitreous) that fills the inside of the eye.

What does this symptom mean?

Although many people have occasional floaters, the sudden onset of many new floaters with or without flashes is an important sign of abnormal pulling on the retina by the vitreous. Sometimes, the retina tears and may cause loss of vision from detachment of the retina. At other times, floaters may persist and chronically interfere with vision.

What causes floaters?

Floaters are usually due to degeneration of the vitreous gel in the eye from aging. Over time, the vitreous shrinks, condenses, and pulls away from the retina. The condensation causes fibers and cellular clumps to pull away from the retina and float freely inside the eye. The shadow of these opacities is what we see as floaters. Other causes of floaters include trauma, bleeding, retinal breaks and detachment, eye surgery, inflammation, and cancer (very rarely).

What can be done about floaters?

It is important to have a thorough dilated eye examination to determine the cause of floaters. Treatment is dictated by the cause of the floaters. If there is no serious underlying cause (retinal break, retinal detachment, etc.), no treatment may be needed. New floaters often fade without treatment. It can be helpful to avoid tracking or following floaters to allow your brain to ignore them. Floaters are less obvious in a darker environment, so wearing sunglasses outdoors may help minimize symptoms of floaters. Stress and depression appear to aggravate the symptoms of floaters and may be treated separately.

YAG Laser Treatment: A special laser may be useful in some cases of persistent floaters. It is an office treatment in which the laser in used to break the floating fibers and clumps into smaller fragments in the vitreous of the eye. Although it may help, YAG laser does not eliminate floaters. Repeat treatments are frequently necessary. Complications may include bleeding, increased floaters, retinal breaks and retinal detachment, which may require surgery to prevent blindness. There is limited evidence on the safety and effectiveness of YAG laser for floaters and it may not be covered by insurance. YAG laser may result in loss of vision/loss of the eye.

Vitrectomy Surgery: Vitrectomy is a surgery performed in the operating room. It is commonly used to treat serious problems of the vitreous and retina. It is very effective at reducing or eliminating floaters. However, complications include bleeding, infection, retinal break and retinal detachment, which may require surgery to prevent blindness. Serious complications occur in 1-2% of eyes reported in most studies, although some reports suggest the risk of complications may be as high as 10%. The most common problem with vitrectomy is cataract formation. After vitrectomy, cataract may develop over months to years and often requires cataract surgery. Glaucoma has been reported years after vitrectomy, but the exact incidence is not known. Vitrectomy surgery may result in loss of vision/loss of the eye.

For most patients the best course of action is observation of floaters without treatment at first. If symptoms persist and significantly interfere with vision despite 6-12 months of observation, treatment may be helpful. Most patients report good results with vitrectomy, but the possibility of complications must be carefully considered and accepted prior to embarking on surgery.

For a telemedicine consultation with Dr Pautler, please send email request to spautler@rvaf.com. We accept Medicare and most insurances in Florida. Please include contact information (including phone number) in the email. We are unable to provide consultation for those living outside the state of Florida with the exception of limited one-time consultations with residents of the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Minnesota, and Washington.

Copyright 2019-2022 Designs Unlimited of Florida. All Rights Reserved.