What is HTLV1?

HTLV1 is a virus that causes HTLV1-associated uveitis. It is an abbreviation for human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. First isolated in 1980, HTLV1 belongs to the retrovirus group that also includes the virus that causes HIV/AIDS. Retroviruses are called “retro” because they use a pathway to reproduce that is the reverse of what most organisms use. The genetic map of retroviruses is RNA, which is converted inside host cells to DNA by a special enzyme (reverse transcriptase). The host cell is then directed to produce more virus particles. HTLV1 is called “lymphotropic” because it tends to infect lymphocytes, which are a type of white blood cell involved with immunity (see Legrand).

How and where do you get exposed to HTLV1?

Because most people with HTLV1 infection remain without symptoms, they carry the virus and spread it to others by sexual contact (semen), shared blood (e.g. IV drug-shared needles, organ transplantation), and by breast milk. HTLV1 is found in most frequently in people from Brazil, Japan, sub-Saharan Africa, Honduras, Iran and the Caribbean islands. However, due to international travel, HTLV1 may be found anywhere in the world.

What problems does HTLV1 cause?

Many people who are exposed to HTLV1 develop no symptoms. However, because HTLV1 affects white blood cells, it may cause autoimmune conditions, as well as blood cancer. For example, autoimmune conditions include seborrheic dermatitis (infective rash), paralysis (tropical spastic paresis), and uveitis (see Schierhout). Examples of blood cancer include T-cell lymphoma and leukemia.

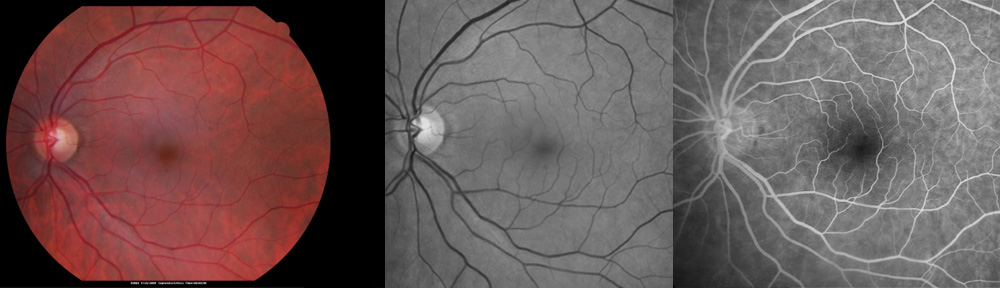

What is Uveitis?

Uveitis (pronounced, “you-vee-EYE-tis”) is a general term used to describe inflammation inside the eye. The uvea is the name given to the layer of tissue in the eye that has a brown color (melanin pigment) and blood vessels, which serve to provide blood supply and protect the eye from excessive light. The uvea can be divided into separate parts, which perform different functions in the eye: the iris, the ciliary body, the pars plana, and the choroid (see anatomy of the eye). Therefore, in any one patient uveitis is usually given a more specific name depending on where most of the inflammation is located in the eye. Sometimes, uveitis affects tissues not considered a part of the uvea.

What type of uveitis is most common with HTLV1?

Intermediate uveitis is the most common type of uveitis caused by HTLV1. In intermediate uveitis the inflammation mainly centers in the vitreous gel (the clear gel that fills the eye). This type of uvetiis is called intermediate because it affects the middle or intermediate part of the eye. That is, the vitreous gel fills the eye and is located in an intermediate position between the front and the back of the eye. Vitritis and pars planitis are other names for intermediate uveitis.

Who is most likely to develop HTLV1-associated uveitis (HAU)?

The age group most likely to be affected by HAU is between 20-49 years; however, any age group may develop HAU (see Mochizuki). Female are affected by HAU twice as often as males (see Takahashi). It appears that the eye inflammation (uveitis) is caused by the effect of HTLV1 infection on the behavior of white blood cells (lymphocytes), rendering them more likely to mistakenly attack the eye (see Mochizuki). HAU may occur with or without other ocular inflammatory conditions, such as thyroid eye disease (see Nakao). Likewise, HAU may occur with or without non-ocular HTLV1-associated conditions, such as paralysis, rash, or blood cancer.

What are the symptoms of HTLV1-associated uveitis (HAU)?

The most common symptoms include tiny floating spots which move or “float” in the vision. They are usually numerous and may cause a veil-like appearance in the vision. Sometimes blind spots, blurred vision, distortion, or loss of side vision occurs. The eye may be painful, red, tearing, and light sensitive if other parts of the eye are also inflamed (5-10% of cases). Symptoms may be mild or they may be severe and disabling. Only one eye is affected in about half of all cases of HAU (see Takahshi).

How is HTLV1-associated uveitis (HAU) diagnosed?

Diagnosis can be difficult. Blood tests are performed to identify HTLV1 infection in patients with findings that suggest HAU. One FDA-approved test is produced by MP Biomedicals Diagnostics: HTLV blot 2.4 (EIA). Sometimes, accurate diagnosis requires multiple tests.

How is HTLV1-associated uveitis (HAU) managed?

There is no cure for HTLV1 infection. To limit the damage from inflammation, HAU is treated with anti-inflammatory medication in the form of eye drops, injections, or pills. When pills are used, the eye doctor may coordinate medical care with the expert assistance of a rheumatologist. Rarely, surgery is required to treat uveitis. Episodes of inflammation may last from weeks to many years. HAU is a serious eye problem and may result in loss of vision (see Takahashi). However, by seeing your eye doctor and taking the medications exactly as recommended, damage to your vision can be minimized. Most people with HAU keep good vision (See Nakao). In some cases, HAU may go away, but return at a future date in about 50% of cases (see Takahashi). Therefore, if you become aware of symptoms of uveitis in the future, do not hesitate to contact your doctor.

For a telemedicine consultation with Dr Pautler, please send email request to spautler@rvaf.com. We accept Medicare and most insurances in Florida. Please include contact information (including phone number) in the email. We are unable to provide consultation for those living outside the state of Florida with the exception of limited one-time consultations with residents of the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Minnesota, and Washington.

Copyright © 2023 Designs Unlimited of Florida. All Rights Reserved.